America’s Budget Is on Autopilot

New research indicates budget process preserves past commitments without adapting to present circumstances.

According to new research published by scholars at the University of Virginia, America’s recent federal budgets aren’t being updated to reflect deteriorating fiscal circumstances.

“Our budget has become more about preservation than medium or long-term planning,” explains Nicholas Whitener, who co-authored the study with professor James Savage.

Their analysis compares fiscal years 2018 and 2025, periods when Republicans had unified control of government, to study how the budget process functions when a single party controls the outcome.

Despite different economic landscapes at the time, they found a similar pattern; rather than proactively reacting to inflation, rising interest costs, or shifts in economic growth, lawmakers prioritized maintaining existing commitments without confronting politically difficult tradeoffs.

In short? We’re affirming the past, while declining to plan for the future.

Performing Discipline (Without Imposing It)

At a glance, Washington looks busy.

The White House announces priorities. The House and Senate pass budget resolutions. And all the while, pay-as-you-go requirements, deficit limits, and spending caps are still on the books.

But in practice, the study’s authors argue the rules meant to constrain spending have become rituals giving the appearance of discipline, while doing little to enforce it.

“We expected polarization,” Whitener says. “But we didn’t expect that we’re just going to keep adjusting rules that were supposed to bind the budget. They’re getting disregarded based on political will.”

The procedural mechanics of budgeting are still running, but the purpose has been lost over time. Instead of adapting to new realities, Congress creates exceptions to rules in order to hold onto old priorities — tax cuts, defense, and entitlements — while avoiding politically painful choices.

Savage, who has studied budgeting since the 1980s, says the change reflects a deeper shift in how both parties govern.

“You have a presidency and a Congress that want to maintain without going through a lot of strife and struggle, like we’re doing with the shutdown right now,” Savage says. “They’d like to preserve [the budget], and the process allows for that to happen.”

What’s the Limit?

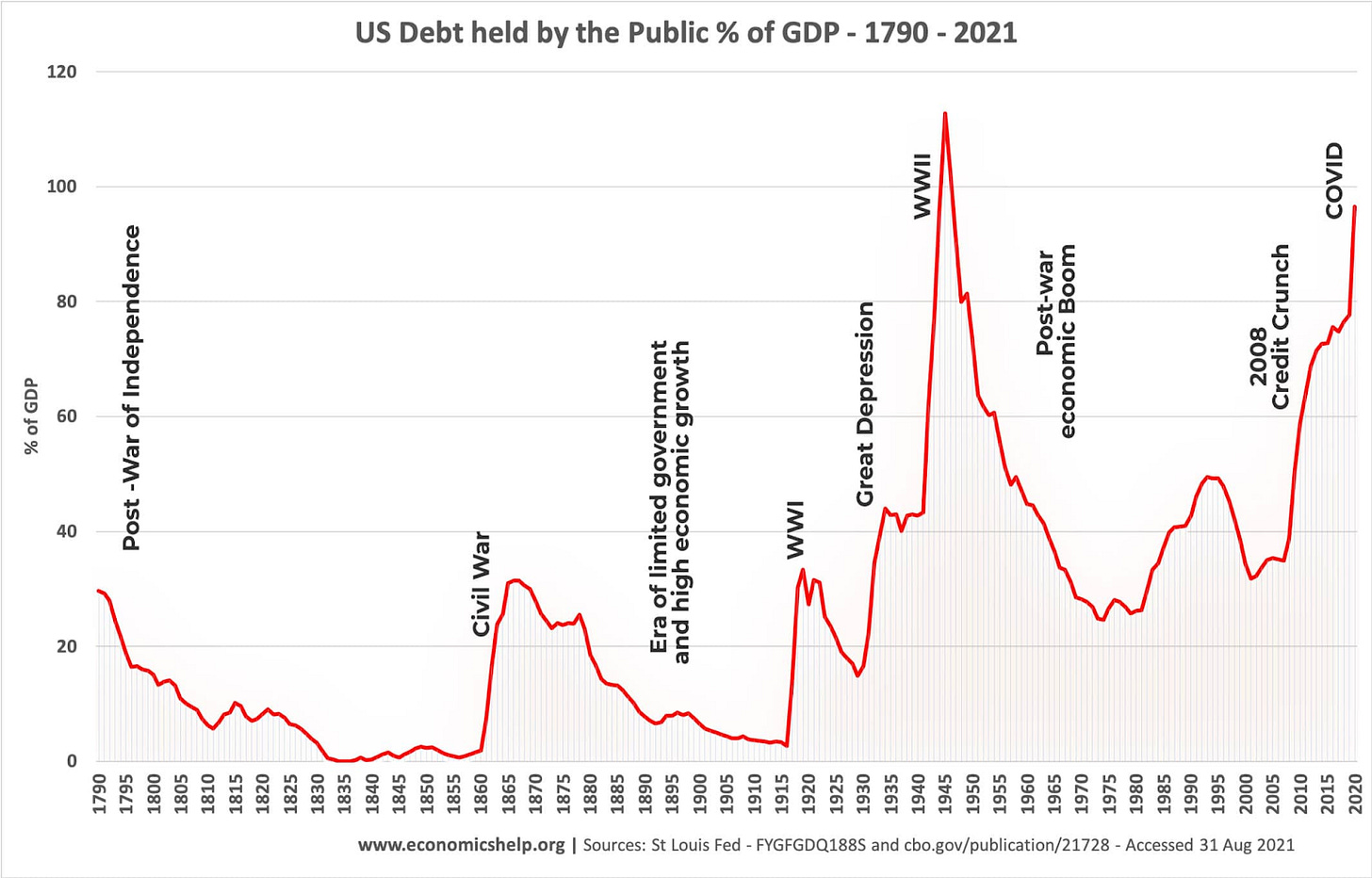

America has never been completely debt-free.

Moreover, no country on Earth is, either. It’s perfectly normal for countries to carry some debt while running deficits in some years, and surpluses in others. Still. Even under that generous framing, at some point, too much is too much.

But where is the limit?

Economic literature analyzes that question through several theoretical frameworks.

“Micro theory says to balance the budget and keep the government out of it,” Savage explains. “Then there’s Keynesianism and supply-side economics, both of which tolerate high deficits for different reasons. We also have modern monetary theory, which tolerates huge national debts, but even then, there’s a threshold. And so the question is, what’s the tipping point?”

Unfortunately, theory can’t point to any single critical point. Ray Dalio’s Principles for Navigating Big Debt Crises includes a compendium of the worst debt disasters of the last 100 years, indicating that losing a major war predicates many debt crises and hyperinflationary events, but that analysis is outside the scope of pure macro theory.

However, Whitener and Savage argue that America’s problem is about more than numbers; it’s about institutions. The budget process still performs the motions of discipline, yet no longer enforces it.

And if the system itself is unresponsive, the question becomes how to fix it.

Options for Reform

One issue is how easily a single party can take control of reconciliation; all it takes is a simple majority in the Senate — 51 votes — to pass a budget. The low vote threshold discourages compromise between parties, and is ripe for abuse by whoever is in power.

Whitener has a favored remedy: “Constitutional reforms would likely be more effective, since politicians would need a super majority to change the rules.”

It’s hard to imagine that passing these days, but there’s at least a precedent; the many EU countries have constitutionally enforced automatic correction mechanisms.

And in lieu of such a sweeping change? Whitener jokes, “If you really want to balance the budget, make congressmen ineligible for reelection if the deficit exceeds a certain threshold. They’d be forced to prioritize fiscal responsibility.”

Whitener and Savege’s research appeared in Public Budgeting and Finance.

Our stories may be republished online or in print under Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. We ask that you edit only for style or to shorten, provide proper attribution and link to our website. AP and Getty images may not be republished.